By Carl A. Brasseaux

The Acadian diaspora has been the subject of intense scrutiny by both popular and scholarly writers since the publication of Longfellow’s Evangeline in 1847. These writers have focused their attention upon the continuing debate over the moral and political aspects of the massive deportation of Acadians from Nova Scotia in 1755, the subsequent distribution of the exiles among the British seaboard colonies, and their ensuing ordeal as de facto prisoners of war. Though of equal importance to the ultimate disposition of the exiles, the post-expulsion wanderings of the Acadians have remained a lost chapter in North American history. Indeed, with the exception of superficial and often inaccurate accounts of the Acadian migration in general histories of the Acadians, no comprehensive view of the Acadian migration to Louisiana existed until the 1980s.

Through the use of major archival collections built by the Center for Louisiana Studies at the University of Southwestern Louisiana and other Gulf Coast repositories, Acadian scholars in Louisiana and elsewhere have patiently pieced together the story of Acadian immigration and settlement in the eighteenth-century Mississippi Valley. What has emerged is the picture of a migration orchestrated in no small part by the Acadians themselves. This image constitutes a radical departure from the traditional views of the Acadian influx, which tended to regard this migration either as a fortuitous happenstance or as the spontaneous migraton of independent groups of exiles to what they considered to be France’s last outpost on the North American continent. This view of the Acadian influx, however, merely belied the one-dimensional vision of historians limited to one archival resource–the general correspondence of Louisiana’s colonial administrators in France’s Archives Nationales. The limited materials formerly available to Louisiana historians also contained numerous gaps in factual documentation, forcing the students of Acadian history to engage in speculation, particularly regarding the dates of arrivals and the settlement patterns of the exiles who sought refuge in Louisiana.

Some scholars, for example had speculated that Acadians began to establish homes in Louisiana as early as 1756, one year after the dispersal. Yet, the vast body of evidence now available to Acadian Studies scholars clearly indicates that the influx of Acadians into Louisiana did not begin until after the promulgation of the Treaty of Paris (ratified on February 10, 1763), which provided an eighteen-month grace period during which Acadians detained in British territory could relocate on French soil, and, at that time Louisiana was still a de facto French territory. The first Acadians to reach Louisiana following their release were twenty individuals from New York. This group included Acadian exiles detained in New York. Arriving at New Orleans in early April 1764, after a brief stopover at Mobile, they were settled by Louisiana’s caretaker French administration along the Mississippi River above New Orleans, near the boundary between present-day St. John and St. James parishes.

These immigrants were followed, in late February 1765, by 193 Acadian refugees from detention camps at Halifax. These Acadians initially sought to relocate at Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti), the French sugar island to which approximately 2,000 of their fellow exiles that fled in late 1763 and early 1764. The refugees from the mainland, however, quickly discovered that life in the Antilles was far more difficult than it had been under English dominion: Acadians were impressed into work details and sent to build the Mole St. Nicolas naval base in the midst of a jungle. The workers were unpaid, receiving as compensation for their labors discarded clothing and inadequate supplies. Their children quickly succumbed to the twin scourges of malnutrition and disease (usually scurvy), while they and their wives fell victim to the climate and endemic fevers. Those Acadians who survived were generally unable to find an economic niche in the island’s plantation economy, which offered few opportunities to independent farmers and became tenant farmers.

As the Halifax Acadians prepared to migrate to the French Antilles, letters from Saint-Domingue reached them carrying reports of maltreatment by French colonial authorities. Repelled by substandard food and clothing, tropical diseases, and social and economic incompatibility with the island’s plantation economy, the Saint-Domingue Acadians resolved to migrate en masse to French-speaking Quebec via the Mississippi Valley, and they invited their cousins in Halifax to join them. Incredible as it may seem, extant sources in Halifax (particularly British intelligence reports) indicate that local Acadians, driven to desperation by the recent reports from St-Domingue and by the British government’s rejection of their efforts to be settled in Canada, embraced this ambitious scheme. Indeed, the Halifax Acadians reportedly anticipated the creation of a major Acadian settlement in Illinois.

Their dreams, of course, were never realized. Although the Halifax Acadians chartered a boat for Saint-Domingue, they subsequently discovered that the vast majority of their confreres were either dead or destitute and unable to afford passage to Louisiana. The Halifax Acadians, led by the legendary Joseph Broussard dit Beausoleil, were thus forced to change ships and continue on alone to the Mississippi Valley. Arriving at New Orleans in late February, 1765 with little more than the clothes they carried on their backs, 193 Halifax Acadians were greeted by a colonial government nearly as destitute as they. Louisiana had been partitioned by the Treaty of Paris (1763) into English and Spanish sectors. Anticipating expeditious occupation of the trans-Appalachian and trans-Mississippi regions respectively by British and Spanish authorities, the French government failed to send material assistance and provisions to Louisiana after 1763. Moved by pity, Louisiana’s French caretaker administrators nevertheless mobilized what limited resources were available, providing each family with land grants, seed grain for six months, a gun, and crude land-clearing implements. The Louisiana government also provided a former military engineer, Louis Andry, to conduct them to the Attakapas District, a frontier post selected for their settlement, and to supervise their establishment.

Though thwarted in their efforts to reach the Upper Mississippi Valley, subsequently harassed by the Attakapas commandant, and decimated by either malaria or yellow fever in the summer and fall of 1765, the Halifax Acadians survived these calamities and, by dint of their unstinting industry, soon prospered. Antonio de Ulloa, Louisiana’s first Spanish governor who arrived at New Orleans on March 5, 1766, stood in awe of his newly established Acadian subjects, who, he observed, literally worked themselves to death to provide for their destitute families as well as their orphaned and widowed relatives. Their persistent labors quickly transformed the region’s semi-tropical jungles into productive farms, and within a decade the exiles enjoyed a standard of living at least equal to that of their predispersal homeland. The Attakapas Acadians were clearly sustained in their Herculean tasks by a desire to create a new homeland not only for themselves, but also for their displaced friends and relatives. Thus, when Ulloa toured the Acadian settlements along Bayou Teche in late spring 1766, the Attakapas settlers sought permission to invite their relatives remaining in exile to join in their good fortune. By this means, the Attakapas Acadians sought to reunite their scattered families in their adopted home, which they now proudly called “New Acadia.”

When Ulloa equivocated, citing the necessity of securing royal authorization, the immigrants characteristically ignored the governor’s pleas to desist and in 1766 and 1767 numerous letters of invitation from Attakapas Acadians circulated widely among the Acadians remaining in exile in Maryland and Pennsylvania. Pooling their meager resources to charter local merchant vessels for Louisiana, hundreds of Acadians–at least 689 of the 1,050 known survivors in Maryland and Pennsylvania–boarded vessels in Chesapeake Bay ports for Louisiana. Arriving at New Orleans, these refugees were greeted as cordially as their predecessors. The colonial government offered them land and material assistance to facilitate their establishment. Amicable relations between the immigrants and their Spanish hosts soured, however, as bitter dispute arose in 1767 and 1768 over the new Acadian settlement sites.

The Acadians had voiced no objections when at least 200 Maryland Acadians had been sent to Cabannocé (present-day St. James Parish) and later to Ascension Parish in the fall of 1766. Cabannocé was already populated by small numbers of Acadians who had either reached the colony in 1764 or who had fled an epidemic in the Attakapas District in the summer and fall of 1765. The proximity of the new settlement sites to those already existing in Cabannocé seemed to augur realization–or at least partial realization–of the Acadian dream of familial renunciation. However, following the arrival of Antonio de Ulloa, Louisiana’s first Spanish governor on March 5, 1766, subsequent waves of Maryland and Pennsylvania Acadians were forcibly dispersed in conformity with Spanish strategic objectives. Extremely concerned about the vulnerability of Louisiana’s eastern frontier to Indian and British encroachment and lacking the troops necessary to protect its extensive borders, Ulloa decided, in May 1766, to utilize the immigrants in the colonial defenses. After May 1766, each wave of immigrants was assigned to a specific site along the Mississippi River which constituted the international boundary between British and Spanish territory. Although the Acadian settlement sites were sometimes isolated and vulnerable to attack, Ulloa hoped that the marksmanship and virulent anglophobia of the immigrants would make the new river posts an adequate first line of defense in the event of Anglo-Hispanic hostilities. Thus, in July 1767, 210 Acadians were assigned to Fort St. Gabriel in present-day Iberville Parish. In February 1768, 149 immigrants were ordered to San Luís de Natchez, near present-day Vidalia, Louisiana.

The dispersal of the immigrants earned the Spanish government the enmity of the Acadian community which, by 1768, had emerged as the predominant cultural group in rural lower Louisiana. As a consequence, the Acadians became active participants in the ouster of Ulloa during the New Orleans rebellion of 1768. Marching into New Orleans on the morning of October 29, 1768, scores of exiles (perhaps as many as 200-300) took up arms to force the Spanish governor’s unceremonious departure from Louisiana.

Spanish control over the colony was restored in August 1769. As a conciliatory gesture, Alejandro O’Reilly, Ulloa’s successor as governor, permitted the disgruntled San Luís de Natchez settlers to migrate to the Acadian settlements along the Mississippi River in late December 1769. This judicious move did much to placate the colony’s Acadian population. But Hispano-Acadian friction and the instability during and following the October 1768 insurrection seems to have discouraged further Acadian immigration into Louisiana. Indeed, while it is possible that a handful of individuals may have found their way to the colony in ensuing years, only one small group of Acadians is known to have arrived in Louisiana between 1768 and 1785. In 1770, a haggard band of thirty Acadians arrived in Natchitoches, Louisiana, after a fifteen-month ordeal of shipboard starvation, mutiny, shipwreck, imprisonment, and forced labor in Spanish Texas, and finally a 420-mile overland trek to Louisiana. After successfully resisting government efforts to settlement them permanently in the Natchitoches area, these refugees established homes first in the Iberville District and later at Opelousas.

The arrival of these immigrants marked the end of the Acadian influx from the Atlantic seaboard colonies. The next wave of Acadian immigration emanated from France, but, once again, Louisiana influences served as the catalyst for migration. In 1766, letters from Attakapas District Acadians to relatives in France had much the same impact as they had previously had on their counterparts in Maryland. Indeed, the approximately 2,500 Acadian refugees in France endured conditions at least as bad, and in some cases, worse than those suffered by the exiles in English captivity. But Acadians in France lacked the resources to take advantage of the opportunity to seek a better life in Lower Louisiana, and the financially embarrassed French government refused to subsidize their relocation as it would benefit only the Spanish crown.

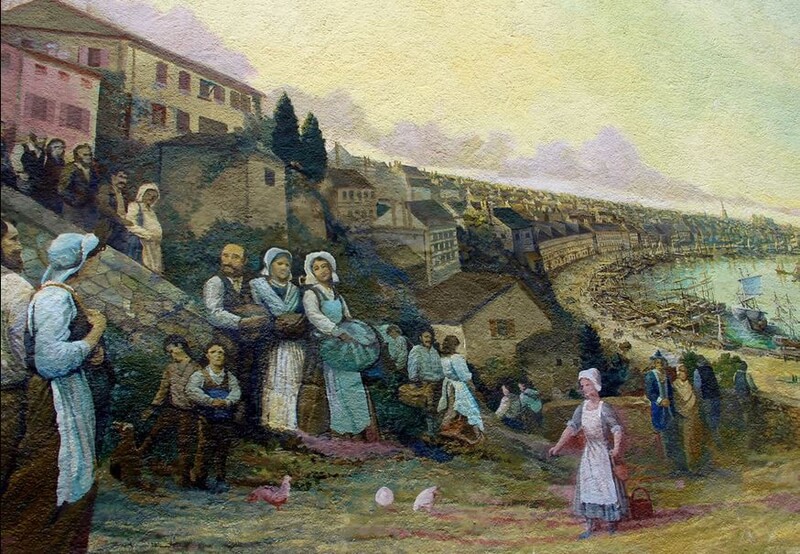

Forced to remain in France and to endure several disastrous resettlement programs in succeeding years, the Acadians maintained their interest in Louisiana through a steady flow of correspondence that crossed the Atlantic in the 1760s, 1770s, and early 1780s. Though none of these letters has survived, numerous references to them in Louisiana, French, and Spanish colonial archvies indicate that many, perhaps most, Louisiana Acadians managed somehow to contact their displaced relatives overseas and, by extolling the virtues of the Mississippi Valley’s slaubrious climate, fertile soil, and abundant unclaimed lands, enticed them to rejoin their kinsmen in the new Acadian homeland. Indeed, the volume of Acadian correspondence reached such proportions that in 1767, exiles at Belle-Ile-en-Mer, France, could describe accurately the location and status of literally hundreds of relatives in St. Pierre and Miquelon, Quebec Province, the Canadian Maritimes, the thirteen English seaboard colonies, and Louisinaa. These letters helped to keep alive the spark of interest in Louisiana colonization among the Acadians in France, and this continuing interest was successfully exploited in 1784 by Henri Peyroux de la Coudrenière, a French soldier of fortune recently returned from Louisiana. The Spanish government had recently sponsored unsuccessful efforts to enlist Iberian Spaniards and Canary Islanders to populate and hispanicize the lower Mississippi Valley and which was actively seeking alternate sources of recruits. By providing colonists for Louisiana, Peyroux anticipated a handsome reward from a grateful Spanish monarch. Working through Acadian shoemaker Olivier Terriot, Peyroux gradually overcame the initial Acadian incredulity and the subsequent resistance of the French government in organizing the largest single migration of Europeans into the Mississippi Valley in the late eighteenth-century. Between mid-May and mid-October 1785, at various French ports, 1,596 Acadians boarded seven New Orleans-bournd merchant vessels chartered by the Spanish government for their transportation.

Upon arrival at New Orleans, the 1785 immigrants were housed in converted warehouses on the western riverbank. While recuperating from the deleterious effects of their trans-Atlantic voyage, they selected delegates to inspect potential home sites in Lower Louisiana. Once the delegates had returned and rendered their reports, the exiles selected–on an individual basis–the settlement in which they wished to reside. Individual interests, however, were often subordinated to those of the group, as eighty-four percent of the immigrants endorsed the sites recommended by their respective delegates. Four of the seven groups of passengers opted to establish communities along Bayou Lafourche, settling between present-day Labadieville and Raceland. Two other contingents of 1785 immigrants selected lands along the Mississippi River near Baton Rouge. The final group of French Acadians accepted lands along lower Bayou des Écores (present-day Thompson’s Creek); this group was later forced to relocate along the Mississippi River and Bayou Lafourche when the 1794 hurricane unleased torrential rains that literally washed away their farms.

The resettlement of the Bayou des Écores Acadians marked the final episode of the major Acadian migration to Louisiana in the late eighteenth century. Nineteen Acadian refugees from St. Pierre and Miquelon, led by Captain Joseph Gravois, are known to have arrived at New Orleans in 1788, but the documentary record is silent about any subsequent arrivals, suggesting that none occurred. An undetermined number of Acadians were undoubtedly among the approximately 10,000 refugees from Saint-Domingue who arrived en masse in New Orleans in the summer and fall of 1809. The evidence indicates, however, that these latter-day Acadian immigrants had already lost much of their ethnic identity and, when forced by circumstances to remain in New Orleans, they were quickly absorbed into the Crescent City’s flourishing Creole community.

The eighteenth-century Acadian immigrants, on the other hand, successfully maintained their identity. The settlement sites of the Acadians along Bayou Lafourche, the Mississippi River, and Bayou Teche provided the exiles a niche in which to reconstruct their shattered society. Cultural rehabilitation was facilitated by the resilience of the Acadian community itself, the numerical superiority of the immigrants in their respective “home” districts, and by the residential propinquity of the immigrants in their waterfront districts. Upon arrival in Louisiana, Acadian families were typically granted concessions with four to six arpents (768 to 1,152 feet) frontage on the nearest waterway with a standard depth of forty arpents (7,680 feet). Colonial Louisiana’s forced heirship laws, which required equitable distribution of property among heirs (and Acadian families were consistently large) upon the demise of landholding parents, quickly reduced the original family lands to narrow ribbons unsuitable for farming. By 1800, many, if not most, individual tracts measured less than one arpent frontage by forty arpents depth. Forced heirship initially worked to preserve Acadian culture by increasing the population density in the original settlement sites at a time when the trickle of non-Acadian immigration into the area threatened to grow into a torrent. Indeed, by the dawn of the nineteenth century, the Acadian community east of the Atchafalaya River consisted of an almost uninterrupted chain of small farmsteads extending along two axis from the lower Lafourche to upper West Baton Rouge Parish, and from upper West Baton Rouge Parish to the St. James-St. John the Baptist Parish boundary.

The residential congestion which helped to preserve Acadian cultural integrity also paradoxically worked to transform their transplanted culture. Though the Acadians constituted a majority in their original districts, New Acadia’s settlements were by no means the Acadians’ exclusive domains. In the Attakapas and neighboring Opelousas posts, small bands of Native Americans and scores of Creoles and recently discharged French soldiers were well established at the time of the Acadian influx. Moreover, in 1779, the Spanish colonial government established a Malaguenian colony at New Iberia, near the overwhelmingly Acadian settlement at Fausse Pointe. East of the Atchafalaya River, the Houma and Chitimacha Indians maintained villages in proximity to their Acadian neighbors at Cabannocé and St. Gabriel while, in the 1770s and early 1780s, many white Creoles from the densely populated German Coast area above New Orleans joined the Acadians in their quest for lands along Bayou Lafourche. Isleños, colonists recruited by the colonial government in the Canary Islands, found homes in the predominately Acadian Lafourche and Iberville districts in 1779. A final cultural element was introduced in the New Acadia settlements in the late 1770s and 1780s when surprisingly large numbers of Acadians began to acquire African slaves, first as wet nurses and later as field hands.

The various components of New Acadia’s polyglot population did not coexist harmoniously: Acadians resented the social pretensions of their white Creole neighbors, who, in turn, were appalled by the exiles’ lack of deference. The Houma tribe, on the other hand, was deeply offended by the government’s decision to settle Acadians on their tribal lands (despite the fact that they, too, were transplanted refugees), and they vented their frustration by almost daily raids on Acadian barnyards and grain stores throughout the 1770s and 1780s. Finally, African bondsmen chafed under the local slave regime, and they reportedly gave their enthusiastic support to an abortive 1785 servile insurrection in the Lafourche District.

These mutual animosities notwithstanding, the rival groups in the New Acadia settlements were compelled by local demography, economics, and topography to interact on a daily basis. This was particularly true of the settlements east of the Atchafalaya River. Whereas the western Acadians of the Opelousas and Attakapas districts could–and many did–escape the intercultural feuding by seeking the isolation of the uninhabited prairies adjoining their bayou country homes, the eastern Acadians were confined by swampy backlands to narrow natural levees along the waterfront. Forced to reside ever closer to their non-Acadian neighbors by the increasing local demographic congestion, the eastern Acadians of the Mississippi River and Bayou Lafourche districts, as well as those remaining along Bayou Teche, gradually found themselves adopting innovations in cuisine and material culture introduced by their neighbors. The so-called “Creole” house–a raised cottage on piers–replaced the Acadian maison de poteaux-en-terre (house of post-in-ground construction) by the 1780s; horse racing, introduced into South Louisiana by a handful of Anglo-American immigrants in the 1780s, was almost immediately preempted by the Attakapas Acadians; the Spanish guitar was adapted to Acadian music and Iberian spices entered the formerly bland Acadian cuisine in the late eighteenth century; by 1803, Indian corn and African okra had found their way into the Acadian diet, but in dishes only remotely resembling their African and Indian progenitors; and, by 1810, a majority of Acadians owned slaves, in emulation of their white Creole neighbors. Indeed, cross-cultural borrowing existed to such an extent that, by the time of the Louisiana Purchase (1803), the basis for a new synthetic South Louisiana culture had been laid.